Managing osteonecrosis risk

New publication from SDCEP gives advice for dental practitioners treating patients at risk of developing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

In 2011, the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) published clinical guidance on the Oral Health Management of Patients Prescribed Bisphosphonates. This was in response to reports in the literature describing a rare side effect in patients treated with these drugs, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ)1.

Bisphosphonates are prescribed to reduce bone resorption in patients with osteoporosis and other non-malignant diseases of bone and to reduce the symptoms and complications of metastatic bone cancer. The drugs persist in the body for a significant period of time; alendronate has a half-life in bone of around 10 years2. As dental extractions appeared to be a risk factor for this oral complication, there was a need for guidance providing clear and practical advice for dentists in primary care on how to provide care for patients prescribed these drugs.

Since 2011, several other drugs have been implicated in what is now referred to as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). The condition has been observed in patients treated with the anti-resorptive drug denosumab which, like the bisphosphonates, is indicated for the prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis and to reduce skeletal-related events associated with metastasis. Another drug class implicated in MRONJ is the anti-angiogenics, which target the process by which new blood vessels are formed and are used in cancer treatment to restrict tumour vascularisation. At the time of writing, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has published Drug Safety Updates warning of the risk of MRONJ for three anti-angiogenic drugs: bevacizumab, sunitinib and aflibercept3,4.

Development of the updated SDCEP guidance

In response to these developments, SDCEP convened a second guidance development group (GDG) in 2015 to update the guidance. The GDG included consultants of various dental specialities, primary care dental practitioners, medical specialists and two patient representatives, who provided feedback on patient views and perspectives.

Pre-publication research was carried out by TRiaDS (Translation Research in a Dental Setting, www.triads.org.uk), who work in partnership with SDCEP, including a national survey of users of the first edition of the guidance and interviews with dentists, pharmacists and doctors. The findings informed the updating of the guidance and have been used as the basis for an implementation questionnaire and a national research audit.

A systematic and comprehensive search of the literature was conducted to inform the recommendations in the guidance. The quality of the evidence and strength of each of the key recommendations is stated clearly in the guidance with a brief justification in the accompanying text. A more in-depth explanation of the evidence appraisal and formulation of recommendations is provided in an accompanying methodology document.

NICE has accredited the process used by SDCEP to produce Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw, which means users can have high confidence in the quality of the information provided in the guidance. Accreditation is valid for five years from 15 March 2016. More information on accreditation can be viewed at www.nice.org.uk/accreditation

Prior to publication, the guidance was scrutinised through external consultation and peer review and it is endorsed by several of the Royal Colleges, Public Health England and Department of Health (Northern Ireland).

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

MRONJ was first reported by Marx in 20031 and is defined as exposed bone, or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula, in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than eight weeks in patients with a history of treatment with anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs, and where there has been no history of radiation therapy to the jaw or no obvious metastatic disease to the jaws5. Risk factors include the underlying medical condition for which the patient is being treated, cumulative drug dose, concurrent treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, dentoalveolar surgery and mucosal trauma. It is important to note that MRONJ is a rare side-effect of treatment with anti-resorptive and anti-angiogenic drugs and, although invasive dental treatment is a risk factor, it does not cause the disease.

At present, the pathophysiology of the disease has not been fully determined and current hypotheses for the causes of necrosis include suppression of bone turnover, inhibition of angiogenesis, toxic effects on soft tissue, inflammation or infection5. It is likely that the cause of the disease is multi-factorial, with both genetic and immunological elements.

Incidence

Estimates of incidence and prevalence vary due to the rare nature of MRONJ. It appears clear that patients treated with anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs for the management of cancer have a higher MRONJ risk than those being treated for osteoporosis or other non-malignant diseases of bone. This is likely to be due, in part, to the substantially larger doses of the drugs that cancer patients receive.

For patients being treated with anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs for the management of cancer, the risk of MRONJ approximates 1 per cent5–9, which suggests that each patient has a one in 100 chance of developing the disease. However, the risk appears to vary based on cancer type and incidence in patients with prostate cancer or multiple myeloma may be higher.

For patients taking anti-resorptive drugs for the prevention or management of non-malignant diseases of bone (e.g. osteoporosis, Paget’s disease), the risk of MRONJ approximates 0.1 per cent or less2,5,7, 10–17, which suggests that each patient has between a one in 1,000 and one in 10,000 chance of developing the disease (Table one).

Patients who take concurrent glucocorticoid medication or those who are prescribed both anti-resorptive and anti-angiogenic drugs to manage their medical condition may be at higher risk.

The incidence of MRONJ after tooth extraction is estimated to be 2.9 per cent in patients with cancer and 0.15 per cent in patients being treated for osteoporosis18.

Risk factors

As outlined previously, the most significant risk factor for MRONJ is the underlying medical condition for which the patient is being treated. Dentoalveolar surgery, or any other procedure that impacts on bone, is also a risk factor, with tooth extraction a common precipitating event19–22. However, MRONJ can occur spontaneously without the patient having undergone any recent invasive dental treatment.

The MRONJ risk in patients who are being treated with bisphosphonates is thought to increase as the cumulative dose of these drugs increases. One study found a higher prevalence of MRONJ in osteoporosis patients who had taken oral bisphosphonates for more than four years compared to those who had taken the drugs for less than four years13. There is currently no evidence to inform an assessment of MRONJ risk once a patient stops taking a bisphosphonate drug. Therefore, it is advised that patients who have taken bisphosphonate drugs in the past should continue to be allocated to the risk group they were assigned to at the time the drug treatment was stopped.

The effect of denosumab on bone turnover diminishes within nine months of treatment completion14, 23. Therefore, patients who have stopped taking denosumab should be considered to still have a risk of MRONJ until around nine months after their final dose. Anti-angiogenic drugs are not thought to remain in the body for extended periods of time.

Chronic systemic glucocorticoid use has been reported in some studies to increase the risk for MRONJ when taken in combination with anti-resorptive drugs20, 24–27. The combination of bisphosphonates and anti-angiogenic agents has also been associated with increased risk of MRONJ20, 28. The risk appears to be increased if the drugs are taken concurrently or if there has been a history of bisphosphonate use.

Despite these risk factors, the majority of patients are able to receive all their dental treatment in primary care, with referral only appropriate for those with delayed healing.

- Fig 1 – SDCEP Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw guidance

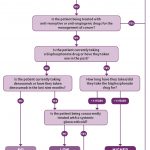

- Fig 2 – Assessment of patient risk

- Fig 3 – Managing the oral health of patients at risk of MRONJ

Guidance recommendations

The aim of the SDCEP guidance is to assist and support primary care dental teams in providing appropriate care for patients prescribed anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs and to encourage a consistent approach to their oral health management. The guidance also aims to empower dental staff to provide routine dental care for this patient group within primary care thereby minimising the need for consultation and referral to secondary care.

Risk assessment

The guidance advises practitioners to assess and record whether a patient taking anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs is at low risk or higher risk of developing MRONJ based on their medical condition, type and duration of drug therapy and any other complicating factors. An up-to-date medical history is therefore essential in identifying those patients who are, or have been, exposed to the drugs and to identify any additional risk factors, such as chronic use of systemic glucocorticoids. Careful questioning of the patient may be required, along with communication with the patient’s doctor, to obtain more information about the patient’s medical condition and drug regimen(s).

The low-risk category includes those patients who have been treated for osteoporosis or other non-malignant diseases of bone with bisphosphonates for less than five years or with denosumab and who are not taking concurrent systemic glucocorticoids. The higher risk category includes cancer patients and also those being treated for osteoporosis or other non-malignant diseases of bone who have other modifying risk factors. Figure two illustrates how risk should be assessed for each individual patient.

The risk of MRONJ should be discussed with patients but it is important that they are not discouraged from taking their medication or from undergoing dental treatment. The guidance includes details of the points which should be covered in such a discussion and patient information leaflets are also available to facilitate this dialogue. As with all patients, the risks and benefits associated with any treatment should be discussed to ensure valid consent.

Initial care

Ideally, patients should be made as dentally fit as feasible before commencement of their anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drug therapy. However, it is acknowledged that this may not be possible in all cases and in these situations, the aim should be to prioritise preventive care in the early stages of drug therapy. Due to their increased MRONJ risk, it is particularly important that cancer patients undergo a thorough dental assessment, with remedial dental treatment where required, prior to commencement of drug therapy. It may also be appropriate to consider consulting an oral surgery or special care dentistry specialist for advice on clinical assessment and treatment planning for these medically complex patients.

As part of this initial management, patients should be given personalised preventive advice to help them optimise their oral health. The importance of a healthy diet, maintaining excellent oral hygiene and regular dental checks should be emphasised and patients should be encouraged to stop smoking and limit their alcohol intake where appropriate. They should also be advised to report any symptoms such as exposed bone, loose teeth, non-healing sores or lesions, pus or discharge, tingling, numbness or altered sensations, pain or swelling as soon as possible.

The guidance recommends prioritising care that will reduce mucosal trauma or may help avoid future extractions or any oral surgery or procedure that may impact on bone. Radiographs should be considered to identify possible areas of infection and pathology and any remedial dental work, such as extraction of teeth of poor prognosis or treatment of periodontal disease, should be undertaken without delay. It may also be appropriate to consider prescribing high fluoride toothpaste for these patients.

Continuing care

Recommendations for continuing care advise practitioners to carry out all routine dental treatment as normal and to continue to provide personalised preventive advice in primary care. For low-risk patients, straightforward extractions and other bone-impacting treatments can be performed in primary care. A more conservative approach is advised in higher risk patients, with greater consideration of other, less invasive alternative treatment options. However, if extraction or other bone-impacting procedure remains the most appropriate course of action, these can be carried out in primary care in this patient group. There is no benefit in referring low or higher-risk patients to a specialist or to secondary care based purely on their exposure to anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs and it is likely to be in patients’ best interests to be treated wherever possible by their own GDP in familiar surroundings.

There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of antibiotic or topical antiseptic prophylaxis specifically to reduce the risk of MRONJ following extractions or procedures that impact on bone29–32. Extraction or oral surgery sites should be reviewed, with healing expected by eight weeks. Evidence of delayed healing at eight weeks should be considered a sign of possible MRONJ. Figure three outlines the management of patients prescribed anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs.

Management of patients with suspected MRONJ

The treatment of MRONJ is beyond the scope of the guidance and patients with suspected MRONJ should be referred to a specialist in line with local protocols. Signs and symptoms of MRONJ include delayed healing following a dental extraction or other oral surgery, pain, soft tissue infection and swelling, numbness, paraesthesia or exposed bone. Patients may also complain of pain or altered sensation in the absence of exposed bone. Although the majority of cases of MRONJ occur following a dental intervention that impacts on bone, some can occur spontaneously. A history of anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drug use in these patients should alert practitioners to the possibility of MRONJ.

Guidance format

The main SDCEP guidance document provides practical advice and recommendations to inform the assessment of the patient’s MRONJ risk, the optimisation of their oral health during the initial phase of drug treatment and their ongoing care. A supplementary Guidance in Brief, which summarises the main recommendations, is also available.

Additional tools have been developed to support the implementation of the guidance, including patient information leaflets and information for prescribers and dispensers. The aim of the patient information leaflets is to make patients aware of the risk of MRONJ, the importance of continuing to take their medication and ways they can reduce their MRONJ risk. The leaflets provide a basis for further communication between the patient and their dentist and, ideally, should be provided to patients identified as being at risk of MRONJ at the commencement of their

drug treatment.

The guidance and the supporting documents are freely available via the SDCEP website (www.sdcep.org.uk).

Future research

MRONJ is a rare condition and consequently there is a lack of high-quality evidence on which to base guidance recommendations. High-quality research studies are required to determine the efficacy of MRONJ prevention protocols, both in the context of routine dental care and in those patents who require an extraction or procedure which impacts on bone. As an adverse drug reaction, MRONJ is monitored by the MHRA (www.mhra.gov.uk) and dental practitioners are encouraged to notify the MHRA of any suspected cases via the Yellow Card Scheme (www.yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Reporting is confidential and patients should also be encouraged to report via the scheme.

It should be noted that the use of anti-angiogenic drugs in cancer is an expanding field, and it is likely that any future medications with these modes of action may also have an associated risk of MRONJ. The establishment of a national database to monitor cases of MRONJ could inform some of the research areas highlighted above and may also serve to identify other drugs which could be implicated in the disease.

As with all its guidance publications, SDCEP plans to review the recommendations in this guidance three years after publication and revise them if new evidence or experience emerges and indicates that this is appropriate.

About the author

Samantha Rutherford is a research and development manager for guidance development within the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP). She has led the development of a number of SDCEP guidance projects and was the project lead for the Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw guidance, which was published in 2017. Samantha has a PhD in medicinal chemistry and prior to her involvement in guidance development, she was a research scientist in the pharmaceutical industry.

References

1. Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2003;61(9):1115-7.

2. Khan SA, Kanis JA, Vasikaran S, Kline WF, Matuszewski BK, McCloskey EV, et al. Elimination and biochemical responses to intravenous alendronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1997;12(10):1700-7.

3. MHRA. Aflibercept (Zaltrap): Minimising the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Drug Safety Update. Apr 2016;9(9).

4. MHRA. Bevacizumab and sunitinib: Risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Drug Safety Update. Jan 2011;4(6):A1.

5. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw -2014 update. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2014;72(10):1938-56.

6. Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, Felsenberg D, McCauley LK, O’Ryan F, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(1):3-23.

7. Kuhl S, Walter C, Acham S, Pfeffer R, Lambrecht JT. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws–a review. Oral Oncology. 2012;48(10):938-47.

8. Lee SH, Chang SS, Lee M, Chan RC, Lee CC. Risk of osteonecrosis in patients taking bisphosphonates for prevention of osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International. 2014;25(3):1131-9.

9. Qi WX, Tang LN, He AN, Yao Y, Shen Z. Risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients receiving denosumab: a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;19(2):403-10.

10. Carmona EG, Flores AG, Santamaría EL, Olea AH, Lozano MPR. Systematic Literature Review of Biphosphonates and Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in Patients With Osteoporosis. Reumatologia Clinica. 2013;9(3):172-7.

11. Grbic JT, Black DM, Lyles KW, Reid DM, Orwoll E, McClung M, et al. The incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients receiving 5 milligrams of zoledronic acid: data from the health outcomes and reduced incidence with zoledronic acid once yearly clinical trials program. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2010;141(11):1365-70.

12. Hellstein JW, Adler RA, Edwards B, Jacobsen PL, Kalmar JR, Koka S, et al. Managing the care of patients receiving antiresorptive therapy for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: executive summary of recommendations from the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2011;142(11):1243-51.

13. Lo JC, O’Ryan FS, Gordon NP, Yang J, Hui RL, Martin D, et al. Prevalence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with oral bisphosphonate exposure. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010;68(2):243-53.

14. Amgen Ltd. Prolia 60 mg solution in a pre-filled syringe: Summary of Product Characteristics 2016. Available from:

www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/23127. Accessed 14/06/17.

15. Rogers SN, Palmer NO, Lowe D, Randall C. United Kingdom nationwide study of avascular necrosis of the jaws including bisphosphonate-related necrosis. The British Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 2015;53(2):176-82.

16. Sammut S, Malden N, Lopes V, Ralston S. Epidemiological study of alendronate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in the southeast of Scotland. The British Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 2016;54(5):501-5.

17. Solomon DH, Mercer E, Woo SB, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S, Treister N. Defining the epidemiology of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: prior work and current challenges. Osteoporosis International. 2013;24(1):237-44.

18. Gaudin E, Seidel L, Bacevic M, Rompen E, Lambert F. Occurrence and risk indicators of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after dental extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2015;42(10):922-32.

19. Fehm T, Beck V, Banys M, Lipp HP, Hairass M, Reinert S, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ): Incidence and risk factors in patients with breast cancer and gynecological malignancies. Gynecologic Oncology. 2009;112(3):605-9.

20. Saad F, Brown JE, Van Poznak C, Ibrahim T, Stemmer SM, Stopeck AT, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(5):1341-7.

21. Vahtsevanos K, Kyrgidis A, Verrou E, Katodritou E, Triaridis S, Andreadis CG, et al. Longitudinal cohort study of risk factors in cancer patients of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(32):5356-62.

22. Yazdi PM, Schiodt M. Dentoalveolar trauma and minor trauma as precipitating factors for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ): a retrospective study of 149 consecutive patients from the Copenhagen ONJ Cohort. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 2015;119(4):416-22.

23. Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, Kendler DL, Miller PD, Yang YC, et al. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(4):972-80.

24. Nisi M, La Ferla F, Karapetsa D, Gennai S, Miccoli M, Baggiani A, et al. Risk factors influencing BRONJ staging in patients receiving intravenous bisphosphonates: a multivariate analysis. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2015;44(5):586-91.

25. Otto S, Troltzsch M, Jambrovic V, Panya S, Probst F, Ristow O, et al. Tooth extraction in patients receiving oral or intravenous bisphosphonate administration: A trigger for BRONJ development? Journal of Cranio-maxillo-facial Surgery. 2015;43(6):847-54.

26. Taylor T, Bryant C, Popat S. A study of 225 patients on bisphosphonates presenting to the bisphosphonate clinic at King’s College Hospital. British Dental Journal. 2013;214(7):E18.

27. Tsao C, Darby I, Ebeling PR, Walsh K, O’Brien-Simpson N, Reynolds E, et al. Oral health risk factors for bisphosphonate-associated jaw osteonecrosis. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2013;71(8):1360-6.

28. Guarneri V, Miles D, Robert N, Dieras V, Glaspy J, Smith I, et al. Bevacizumab and osteonecrosis of the jaw: incidence and association with bisphosphonate therapy in three large prospective trials in advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;122(1):181-8.

29. Ferlito S, Puzzo S, Liardo C. Preventive protocol for tooth extractions in patients treated with zoledronate: a case series. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;69(6):e1-4.

30. Lodi G, Sardella A, Salis A, Demarosi F, Tarozzi M, Carrassi A. Tooth extraction in patients taking intravenous bisphosphonates: a preventive protocol and case series. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010;68(1):107-10.

31. Mozzati M, Arata V, Gallesio G. Tooth extraction in osteoporotic patients taking oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporosis International. 2013;24(5):1707-12.

32. Schubert M, Klatte I, Linek W, Muller B, Doring K, Eckelt U, et al. The saxon bisphosphonate register – therapy and prevention of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Oncology. 2012;48(4):349-54.

Verifiable CPD Questions

Aims and objectives:

- To alert dentists to the publication of SDCEP’s new dental clinical guidance and accompanying tools

- To provide an insight into the background evidence and judgements that support the guidance recommendations

- To give a brief overview of the key recommendations in the new guidance.

Learning outcomes:

After reading this article the reader should:

- Be aware of the drugs associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

- Have gained an understanding of the evidence, clinical experience and other factors that influenced the guidance recommendations

- Be familiar with the key recommendations made in the guidance.

Comments are closed here.