Do endodontic treatments actually work?

Dr Bob Philpott tackles some of the most pertinent questions he has been posed regarding the outcome of endodontics in practice

Depending on what you read, there are various criteria proposed for assessment of endodontic outcome and these differ depending on whether a surgical or non-surgical approach has been used. The European Society of Endodontology proposes the following definition of non-surgical root canal treatment (NSRCT) outcome:

- Healed: Absence of clinical signs and symptoms and a return to normal architecture of the periodontal ligament radiographically.

- Healing: Absence of clinical signs and symptoms and reduction in size of the periapical lesion.

- Failure: Presence of clinical signs/symptoms and/or no reduction in lesion size, increase in lesion size or emergence of a new periapical lesion.

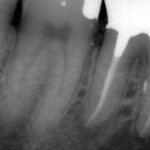

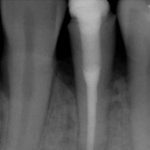

From the literature, it would seem that success rates of NSRCT are relatively high depending on the criteria used yet often teeth exhibiting reduced lesion size are hard to classify. Although Orstavik (1996) highlighted that teeth showing these radiographic signs of healing at 12 month review, continue to heal in almost 90 per cent of cases (Figs 1a and b). For those dubious cases it is important to arrange follow up for anything up to four years and not condemn a tooth to failure too early (Strindberg 1956).

Does survival count?

The stringent outcome criteria outlined above have been used to assess NSRCT for decades. More recently, however, survival rates have been mentioned in the endodontic literature (Salehrabi 2004).

This has partly been driven by the endodontic discipline in order to level the playing field between endodontics and implants. Much of the implant literature uses this less stringent definition of treatment outcome, with survival rates in excess of 90 per cent being reported. The reality is that it is very difficult to compare the two treatment modalities and unnecessary also as both have a place in daily practice life. Direct comparisons, although shining a favourable light on endodontics (Doyle 2006) are also confusing and probably best avoided.

More recently, the term functionality has appeared in the endodontic literature and this may be more relevant to practice. Friedman (2004) described this as a tooth presenting with an absence of clinical signs/symptoms but with evidence of pathosis radiographically. How often do we see patients who, when faced with the prospect of dismantling a tooth which has been in function for decades and exposing themselves to the risk of it being unrestorable, choose to continue to monitor the situation instead? This may pose problems later in terms of potential flare up and possible systemic impacts of oral infection although the evidence supporting the later in the endodontic literature is scarce.

Are cracked teeth doomed to failure?

Diagnosis of and prognostication in relation to cracked teeth is difficult. Where does the crack end? How likely is it to progress? Will it affect longevity? All of these questions spring to mind when we consider this clinical scenario.

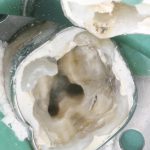

Patients presenting with symptoms of a crack in a vital tooth should always be investigated thoroughly and this often involves removal of the direct restoration, visualisation of the crack under magnification and illumination and possibly a period of stabilisation with a stainless steel orthodontic band. In the cases of root filled teeth, again the tooth should be dismantled and the crack visualized in order to attempt to assess its severity (Figs 2a-c). Care should also be taken to identify and assess any soft tissue signs such as multiple draining sinuses or deep narrow isolated probing defects adjacent to heavily restored root filled teeth. Cracks can often be very difficult to diagnose radiographically unless there is frank separation of the tooth fragments although a characteristic J-shaped radiolucency may indicate a split tooth.

The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) have attempted to classify cracked teeth according to severity, ranging from an enamel infraction up to a split tooth and this is helpful in terms of reaching a diagnosis and labelling these teeth. It does not, however, offer much help in terms of deciding on whether to treat or extract these teeth. Traditionally, it was felt that the presence of a crack on the floor of the pulp chamber often precluded endodontic treatment, but more recent outcome studies have highlighted the importance of the presence of a deep probing defect associated with the tooth as a negative prognostic factor (Tan et al. 2006, Kang et al. 2016) while others have found that extension on to the pulpal floor resulted in greater tooth loss (Sim et al. 2016). So, that just seemingly adds to the confusion.

Most importantly, the patient needs to be made aware of the presence of a crack and its potential effect on outcome. Ultimately, it is the patient who decides, although I would personally caution against attempting to save teeth with extensive cracks due to the detrimental effect this would have on the surrounding bone should the crack propagate and the subsequent effect on the bony site for implant placement.

Does rubber dam actually matter?

Although the use of rubber dam is widely recommended during endodontic treatment, two things become clear when the evidence is examined more closely:

- Rubber dam is not routinely used during treatment. According to Whitworth et al. (2000), 60 per cent of dentists never use it, with factors such as patients’ perceptions, time to apply and a lack of training being cited as obstacles.

- There is actually very little in the literature which highlights the positive impact rubber dam use can have on the outcome of endodontic treatment, with only van Nieuwenhuysen et al. (1994) and Lin et al. (2014) showing a positive association.

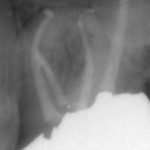

However, this should not mean that we do not recognise the multiple benefits of rubber dam use during endodontic treatment, namely retraction of soft tissues, better visualisation and protection of the airway among them. The reality is that rubber dam makes our job easier and that makes a difference (Fig 3).

What effect do missed canals have?

Uninstrumented and unfilled root canal anatomy can clearly have an effect on endodontic outcome, and nowhere is this more evident than in the case of the second mesiobuccal canal or MB2 in maxillary molars.

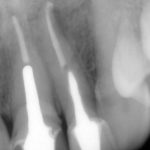

The key to successful identification of root canal anatomy lies in the design and execution of our access cavity. Large, overblown access cavities, incorrect positioning and small contracted cavities lend themselves to problems later. Magnification and illumination are also key with Kulild & Peters showing that almost 10 per cent of MB2 canals were not identifiable without the aid of a dental operating microscope (DOM). They also highlighted the fact that the MB2 is present in excess of 90 per cent of the time (Fig 4a-d).

The effect of missed canals on outcome may be a function of canal configuration in that canals joining before the apex are less likely to have a negative effect. Their presence may also play a strong role in decision-making in failed cases in terms of choosing a surgical or non-surgical approach. Wolcott et al. (2005) discussed the impact of a missed MB2 on prognosis and highlighted its increased incidence in non-surgical re-treatment cases.

- Figures 1a and 1b Pre-operative and six-month review radiographs following root canal re-treatment showing signs of healing

- Figure 1b

- Figure 2a – Photograph showing crack at MB aspect of tooth 36

- Figure 2b Radiograph following endodontic treatment

- Figure 2c Tooth prepared subsequently for full coverage restoration

- Figure 3 Maxillary molar isolated under rubber dam (note stabilisation with orthodontic band and Oraseal used to fill deficiencies in dam)

- Figures 4a-c Radiographs above showing MB anatomy following obturation in both primary and re-treatment cases

- Figure 4b

- Figure 4c

- Figure 4d Photo showing position of MB2 on floor of pulp chamber

- Figure 5a Periapical radiographs showing satisfactory obturation and almost complete resolution of lesion at six-month review

- Figure 5b Periapical radiographs showing satisfactory obturation and almost complete resolution of lesion at six-month review

- Figures 6a-c Radiographs showing teeth restored with fiber post and composite core, direct composite core and cast post and core

- Figure 6b

- Figure 6c

Which factors actually affect the outcome?

Outcome studies have highlighted many factors that affect endodontic outcome with the length of the root filling, its density and the quality of the coronal restoration being common to many of them. Ng et al. (2011) cited 13 factors that can affect the outcome of both primary and secondary NSRCT. Interestingly, many of these factors are related to our treatment of root canal infection and obturation, of course, is merely a surrogate measure of what went before. The key to successful treatment lies in the adherence to strict biological principles (isolation, hypochlorite use, patency, dense obturation to length) and the execution of this clinically (Fig 5).

How important is the coronal restoration?

The role of the coronal restoration is also important. Many papers have discussed this with some proposing the restoration as a more important prognostic factor (Ray and Trope 1995), others emphasising the importance of the restoration (Tronstad 2000) and others wisely stating the importance of both (Hommez et al. 2002).

Ng et al. (2011) describes a number of ‘restorative factors’ that may affect the outcome:

- Presence of temporary vs. cast restoration

- Terminal location of tooth

- Presence of cast post and core

- Missing proximal contacts.

It has been routinely accepted that indirect cuspal coverage for posterior root filled teeth with breached marginal ridges constitutes best practice, although Sequeira-Byron et al. (2015) in their Cochrane review, have questioned the evidence base for this although they stop short of not recommending cuspal coverage clinically.

The issue of cast/metal versus fiber posts is also one which is raised regularly (Figs 6a-c). The issues of root fracture and dentine removal are reported as disadvantages of the former while issues with bonding to root canal dentine are cited by those opposing the use of the latter. Theodosopoulou and Chochlidakis (2009) in their systematic review on the subject reported that carbon fiber posts perform better than precious metal cast posts although there are numerous other sources which are not in agreement with this. The reality is that decisions should be made on a case by case basis based on both canal anatomy and remaining dentine distribution and thickness.

How often should I review the patient?

Although Orstavik found radiographic signs of healing within three weeks post-treatment, it is almost universally accepted that a minimum period of six months should elapse before review is considered. The ESE recommend clinical and radiographic review at one year and continued follow up for a period of four years depending on the initial response.

Fristad et al. reported ‘late successes’ with radiographic signs of healing being evident up to 27 years after treatment. They also caution against labeling radiographic overfills with persistent radiolucencies as failures as delayed healing is often seen in these cases and they are best monitored.

Clinically, we do also sometimes encounter patients who appear to have inexplicable symptoms of discomfort or awareness of a root filled tooth, even in the presence of radiographic signs of healing. Polycarpou et al. (2005) reported the prevalence of persistent pain following successful root canal treatment to be as high as 12 per cent, with a number of factors influencing this including pre-operative tenderness to percussion, a history of chronic pain and presence of pre-operative pain associated with the tooth. We should possibly remember this when consenting patients in certain cases prior to treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the factors affecting the outcome of endodontic treatment, our role in achieving it and the required follow up period and protocol are clear. Unfortunately, despite all of this as Marton and Kiss (2000) outlined in their review paper, root canal treatment is merely a permissive factor for healing and so we do not have direct control over it. We can only try our best and hope that it is good enough.

References

Doyle, Scott L, et al. “Retrospective cross sectional comparison of initial nonsurgical endodontic treatment and single-tooth implants.” Journal of Endodontics 32.9 (2006): 822-827.

Friedman, Shimon, and Chaim Mor. “The success of endodontic therapy healing and functionality.” CDA J 32.6 (2004): 493-503.

Fristad, I, O Molven, and A Halse. “Nonsurgically retreated root filled teeth–radiographic findings after 20–27 years.” International Endodontic Journal 37.1 (2004): 12-18.

Hommez, GMG, CRM Coppens, and RJG De Moor. “Periapical health related to the quality of coronal restorations and root fillings.” International Endodontic Journal 35.8 (2002): 680-689.

Kang, Sung Hyun, Bom Sahn Kim, and Yemi Kim. “Cracked Teeth: Distribution, Characteristics, and Survival after Root Canal Treatment.” Journal of Endodontics 42.4 (2016): 557-562.

Kulid, James C, and Donald D Peters. “Incidence and configuration of canal systems in the mesiobuccal root of maxillary first and second molars.” Journal of Endodontics 16.7 (1990): 311-317.

Lin, Hui-Ching, et al. “Use of rubber dams during root canal treatment in Taiwan.” Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 110.6 (2011): 397-400.

Marton, IJ, and C Kiss. “Protective and destructive immune reactions in apical periodontitis.” Oral Microbiology and Immunology 15.3 (2000): 139-150.

Ng, YL, V Mann, and K Gulabivala. “A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of non-surgical root canal treatment: part 2: tooth survival.” International Endodontic Journal 44.7 (2011): 610-625.

Ørstavik, D. “Time-course and risk analyses of the development and healing of chronic apical periodontitis in man.” International endodontic journal 29.3 (1996): 150-155.

Polycarpou, N, et al. “Prevalence of persistent pain after endodontic treatment and factors affecting its occurrence in cases with complete radiographic healing.” International Endodontic Journal 38.3 (2005): 169-178.

Ray, HA, and M Trope. “Periapical status of endodontically treated teeth in relation to the technical quality of the root filling and the coronal restoration.” International Endodontic Journal 28.1 (1995): 12-18.

Salehrabi, Robert, and Ilan Rotstein. “Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: an epidemiological study.” Journal of Endodontics 30.12 (2004): 846-850.

Sequeira-Byron P, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, Nasser M, Alrowaili EF. Single crowns versus conventional fillings for the restoration of root-filled teeth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD009109. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009109.pub3

Sim, Irene GB, et al. “Decision Making for Retention of Endodontically Treated Posterior Cracked Teeth: A 5-year Follow-up Study.” Journal of Endodontics 42.2 (2016): 225-229.

Strindberg, Lars Z. The dependence of the results of pulp therapy on certain factors: an analytic study based on radiographic and clinical follow-up examinations. Vol. 12. Mauritzon, 1956.

Tan, L, et al. “Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution.” International Endodontic Journal 39.11 (2006): 886-889.

Theodosopoulou, Joanna N, and Konstantinos M Chochlidakis. “A systematic review of dowel (post) and core materials and systems.” Journal of Prosthodontics 18.6 (2009): 464-472.

Tronstad, L, et al. “Influence of coronal restorations on the periapical health of endodontically treated teeth.” Dental Traumatology 16.5 (2000): 218-221.

Van Nieuwenhuysen, JP, M Aouar, and William D’Hoore. “Retreatment or radiographic monitoring in endodontics.” International Endodontic Journal 27.2 (1994): 75-81.

Whitworth, JM, et al. “Use of rubber dam and irrigant selection in UK general dental practice.” International Endodontic Journal 33.5 (2000): 435-441.

Wolcott, James, et al. “A 5 yr clinical investigation of second mesiobuccal canals in endodontically treated and retreated maxillary molars.” Journal of Endodontics 31.4 (2005): 262-264.

About the author

Dr Robert Philpott, BDS MFDS MClinDent MRD (RCSEd), qualified from Cork Dental School in 2003 and completed his endodontic training at Eastman in London in 2009. He has worked as a specialist in endodontics in Ireland, London and Australia. He currently divides his time working as a consultant in endodontics at Edinburgh Dental Institute and in private practice at Edinburgh Dental Specialists.

Verifiable CPD Questions

Aims & objectives:

- To address the questions that may arise in relation to achieving a successful outcome during non-surgical root canal treatment

- To discuss relevant clinical issues

- To provide tips to help optimise outcomes in the clinical setting

Learning Outcomes

At the end of the article our readers will:

- Have an understanding of the factors related to successful endodontic outcomes

- Identify the most important clinical factors needed to achieve the best results

- Be able to apply a biological understanding of endodontics to their day-to-day practice

- Recognise the importance of long-term follow-up of patients following root canal treatment.

Comments are closed here.