Raising our suspicions: could this be an oral cancer?

With the number of cases on the increase, dentists have a key role to play in the early detection of the disease and in raising patients’ awareness of the risks of cancer

The early detection of oral cancer has now become a recommended topic by the General Dental Council (GDC) for Continuing Professional Development (CPD).

The importance of raising our suspicions for any lesion was brought home to me as I was writing this paper. The brother of a medical friend had just been diagnosed with mouth cancer at the age of 54. No obvious risk factors were present and yet, despite going to his GP with a persistent ulcer, it was more than two months until he was referred.

My doctor friend called me for advice regarding her brother on the day I received feedback on a lecture I’d given to some medical students doing their cancer prevention module. Despite presaging my lecture with the reasons why medics needed to be as genned up on this as the dentists, one student still felt it was more important for dentists than themselves (presumably a reflection on the numerous other topics competing for their attention within the medical curriculum).

Studies have shown that there is a 40 per cent underestimation of what people claim they drink, when compared with actual alcohol sales

Graham Ogden

The GDC based their recommendation in part due to an increasing number of patients who are claiming (rightly or wrongly) that their dentist failed to diagnose their mouth cancer and, as such, are suing them for negligence. Other reasons include an increasing number of cancer cases (hence increased likelihood of seeing a patient with oral cancer,) and the life-threatening nature of this disease (the later it is diagnosed, the worse the outcome for the patient).

It used to be an anecdote that a dentist might only see two cases of oral cancer in their entire career. But was or is that actually true? There may be a need to recalculate this because, although there are many more dentists now than, say 30 years ago, the incidence of oral cancer has risen sharply (threefold) over that time period without a marked increase in size of population. We recently recalculated this and arrived at a conservative estimate of one case every 10 years, with two potentially malignant lesions seen every month.1

What can we do to help minimise such an event?

- Reasons why a patient may pursue a case of negligence against a dentist in respect of oral cancer are:

- Failure to identify a lesion in the mouth

- A failure to consider the lesion might be a cancer and thus miss the opportunity to make an early diagnosis

- Failure to refer to a specialist

- Claims for damages following the consequences of a failure to detect the cancer at an early stage

- A perception by the patient that the dentist had not taken their concerns seriously.

Key questions to consider when assessing the malignant potential of an oral lesion:

1. What risk factors are present?

Tobacco

While the number of cigarettes consumed within the UK has dropped profoundly over the last 25 years or so (from a staggering 102 billion in 1990), the reduction in the number of smokers has not been as dramatic. Approximately 20 per cent of the population in Scotland still smoke. Although novel approaches to certain groups have had some success (e.g. “Give it up for baby” – a smoking cessation intervention for pregnant women in Scotland, organised by Paul Ballard and NHS Tayside) – there is still a long way to go.

Clinicians should be actively involved in raising awareness of the potential detrimental effects of smoking on oral health and giving smoking cessation advice. A key question to ask the patient with a clinically suspicious lesion is “Do you smoke?”

At least 75 per cent of oral cancers are associated with tobacco use.

With the increase in cost, many people are turning to hand-rolled cigarettes because they are cheaper but they may lack an effective filter. Key additional questions include recording type of tobacco use, number of years they have smoked and daily quantity consumed.

Don’t forget ecigarettes, although in theory devoid of the usual carcinogens found in tobacco, are still unregulated and hence their exact content is not always known. More than three million ecigarettes were sold in the UK in 2012. However, many patients find Allen Carr’s book Easy Way to Stop Smoking an effective alternative to other techniques such as nicotine replacement therapy.

Alcohol

As with tobacco, it is worth asking about their use of alcohol, as this is an important risk factor for oral cancer, particularly when combined with tobacco use. The Government, and indeed all the Royal Colleges, support the guidance as regard low-risk drinking. For men this is currently considered as no more than four units in a day or 21 units in a week (for women it is no more than three units in a day and 14 units in a week) with at least two days free of alcohol.

Obtaining a reliable alcohol history isn’t always easy, partly because many patients don’t know the alcohol unit content of what they drink, but also because we are often economical with the truth. Studies have shown that in the UK there is a 40 per cent underestimation of what people claim they drink, when compared with actual alcohol sales.

We have gathered data regarding drinking habits and understanding of alcohol guidelines over several years during our annual Mouth Cancer Awareness Week campaigns at the University of Dundee. There is a tendency for students to underestimate the number of units of alcohol in a pint of beer. When this is combined with the frequency that they admit to binge drinking (defined as at least six units in any one session for women, and at least eight units for men), then many students would appear to be drinking at a level that would trigger a brief alcohol intervention.

The development of an appropriate intervention for dental practice is currently being explored2.

Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)

The subtypes ( associated with both cervical cancer and oral cancer) are HPV 16 and HPV 18. It is more often associated with oropharyngeal cancer than oral cancer. The virus interferes with the tumour suppressor gene, P53 that protects us against cancer .The HPV virus disables the protective effect of the P53 gene allowing those mutations which retain the cell’s ability to replicate, to further develop on its journey to potentially becoming a cancer. Infection with HPV can be transitory , with HPV 16 and HPV 18 acquired through oro-genital contact. Perhaps not the easiest question to ask of a patient visiting their dentist! Jaime Winstone’s BBC3 programme “Is oral sex safe?” is well worth viewing.

Don’t forget that a patient doesn’t have to have an obvious risk factor.

2. What is its colour? (‘Red is a mean mean colour’)

While I’m sure Steve Harley didn’t have oral cancer in mind when he wrote that song, it seems peculiarly apposite. Red is a far more significant colour when it comes to early manifestation of oral cancer, yet leukoplakia is often considered the most frequent precancerous lesion. By focusing on the white element, the issue of any surrounding erythema may be lost. Although much is made of the white patch its malignant transformation rate is probably less than five per cent whereas that of the erythroplakia is at least 80 per cent (far more significant).

Having said that, the most significant leukoplakia’s are those that are large and non-homogenous. Far more important and more frequently associated with asymptomatic early oral cancer are the so-called speckled leukoplakia’s (erythroleukoplakia).

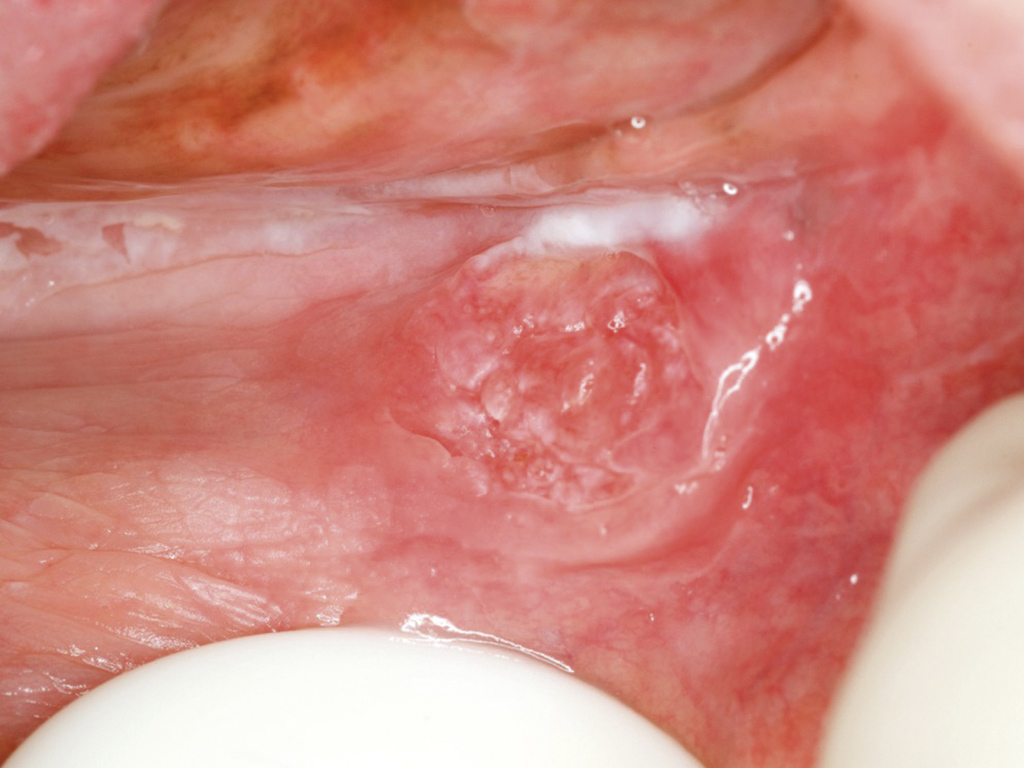

3. What does the early oral cancer look like?

The early asymptomatic cancer presents in a far more subtle way than many of the textbooks might suggest. The identification of an oral cancer that has raised, rolled hard edges surrounding an area of ulceration that is oozing blood is an advanced lesion that hopefully no one would miss. Unfortunately, by the time is has that appearance, such an advanced lesion has had plenty of opportunity to either invade surrounding tissues (such as bone) or metastasise to local, regional or distant lymph nodes.

Our attention as clinicians should be to focus on raising our index of suspicion. High-risk sites in the UK are the so-called non-keratinising sites such as ventral tongue and floor of mouth. However, the routine screening and recording in the notes of the entire oral mucosa should be mandatory, not only to help to detect an early lesion, but also to help protect yourself from any claims of negligence that you failed to detect the cancer at an early stage. Such a task that takes minimal time, requires no fancy expensive equipment, but yet could make such a difference to the patient’s prognosis (if a cancer is there), is ignored at our peril. (The use of dyes or techniques based upon fluorescence or cytology are still being evaluated or have not proved to have the sensitivity or specificity to become adopted as routine tests).

Conclusion

The early detection of an oral cancer can quite literally save that patient’s life. In helping to raise your index of suspicion when assessing the malignant potential of an oral lesion we should consider:

- What risk factors are present? (NB tobacco and alcohol, HPV?)

- What is its colour? (NB importance of red)

- How long has it been present? (Review the patient to ensure it has improved/resolved within two weeks or arrange urgent referral when cancer is suspected)

- Is it painful? (Pain is often a relatively late manifestation hence a non-painful ulcer should arouse suspicion)

Remember, the early lesion is often asymptomatic (no pain, no ulceration, no bleeding). Remember too that a patient is never too young to get oral cancer. One in 10 cases now arise in those below the age of 45 years (see the Ben Walton Trust www.benwaltontrust.org).

- Typical textbook appearance of an advanced oral cancer Reproduced from Dental Update (ISSN 0305-5000), by permission of George Warman Publications (UK) Ltd

- Note atrophic red area of early cancer surrounded by satellites of white keratoses

- Early oral cancer affecting buccal sulcus. Note the areas of diffuse keratosis and atrophy surrounding the ‘whorl’ of slightly raised, reddened mucosa

About the author

Professor Graham R Ogden, is professor of oral surgery and honorary consultant in oral surgery within the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Clinical Sciences at the University of Dundee Dental Hospital and School.

References

Aspects of this paper were included in the recently published paper, Ogden G Oral cancer: what do we need to know and do? Dental Nursing 2015 11(5) 275–278.

- G. R. Ogden, C. Scully, S. Warnakulasuriya & P. Speight Oral cancer: Two cancer cases in a career? British Dental Journal 218, 439 (2015) Published online: 24 April 2015 | doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.302

- Shepherd S, et al Current practices and intention to provide alcohol related health advice in primary dental care British Dental Journal 211:322-3 2011 doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.822

By word of mouth

For those who wish to get involved in raising awareness of oral cancer, for example during Mouth Cancer Awareness Week in November each year, then see the link to “You too can raise awareness of mouth cancer” at http://bit.ly/BWTpdf

The Ben Walton Trust has done much to raise both professional as well as public recognition of the disease. There is also another Scottish-based charity – https://letstalkaboutmouthcancer.wordpress.com – which aims to achieve greater recognition of the disease within the general population.

While we should all maintain our suspicions regarding any lesion within the oral cavity, we can do nothing about the patient that presents to their GP in preference to their GDP. Or can we?

I would suggest that we, as dentists, need to explain to our patients every time they attend that we are screening their mouth for any suspicious changes that they may not even be aware of; that we are trained to examine the whole mouth, not just the teeth and gums.

Establishing links with local GPs should benefit both clinicians and patients. The days when colleagues felt referral for a second opinion implied they were not capable have surely gone. But, to do that, we first have to see the lesion, i.e. examine the whole mouth and then consider that it might be an early cancer. It is for this reason that it is entirely right that oral cancer has become a recommended topic for CPD by the GDC and serves as a reminder that every time a patient attends, there must be a careful clinical examination of the entire oral mucosa.

Where cancer is suspected, the patient should be urgently referred to be seen within two weeks. Furthermore, with an increase in oropharyngeal lesions that may spread to cervical lymph nodes, it is more important than ever that dentists should carefully check for swellings in the neck. This may be particularly important in irregular attenders, as that may be the one chance for early detection, which could quite literally save that person’s life.

Comments are closed here.