Not another global pandemic!

During the first COVID-19 lockdown, as the owner of Platt & Common in Stirling, I took a moment to clear out an old cupboard … and came to realise that the practice had been through this before

As the practice doors closed on the evening of Friday 20 March 2020, I had no idea that it would be more than 100 days before those same doors would be opening to patients, albeit only for emergencies. That lunchtime we had sat together as a practice. Domino’s wanted to thank all those working in the NHS by offering discounted pizzas that day. Looking around at all the dentists and nurses eating together in our staff room, I couldn’t help but wonder when we would be able to do such a thing again.

The TV screen in the waiting room had been set to the BBC News channel all week as we tried to keep up with the daily newsfeed about the virus that was coming our way. Twitter and Facebook sites were a ready source of information as we waited for the Chief Dental Officer to make a statement. Tom Ferris’s letter on 17 March to all GDPs in Scotland advised that “contingency measures have been put in place to preserve the integrity of GDS as a result of substantial disruption to service provision due to the escalation of the Covid-19 outbreak in Scotland.” As with all practices in Scotland we downed tools, completed, and then submitted, our ‘Business Continuity Plan’.

We continued to see patients but there had been a growing sense of unease that week, not just among the staff, but with patients who had begun to cancel their routine examination appointments as well as some treatments. My last patients on that Friday were a family of three and the father, slumping into the chair, looked at me, and said: “This is all a load of nonsense, isn’t it?”

The day finished with all the staff sitting together around our waiting room and whilst I did not know what to tell them, I knew that I did not want them to come into work on the Monday. It was apparent with the closure of bars and restaurants that day that we were heading into lockdown, and I wanted everyone to stay at home to be safe. The ‘Stay at Home, Protect the NHS’ message had been used all that week by the UK Government, and it seemed appropriate to use this message at this time. In a final gesture of solidarity and in a vain attempt to stem the tears that were flowing from a number of staff members, we had a group hug. The number of coronavirus cases in Scotland had reached 266 that Friday and there had been 108 deaths in the UK.

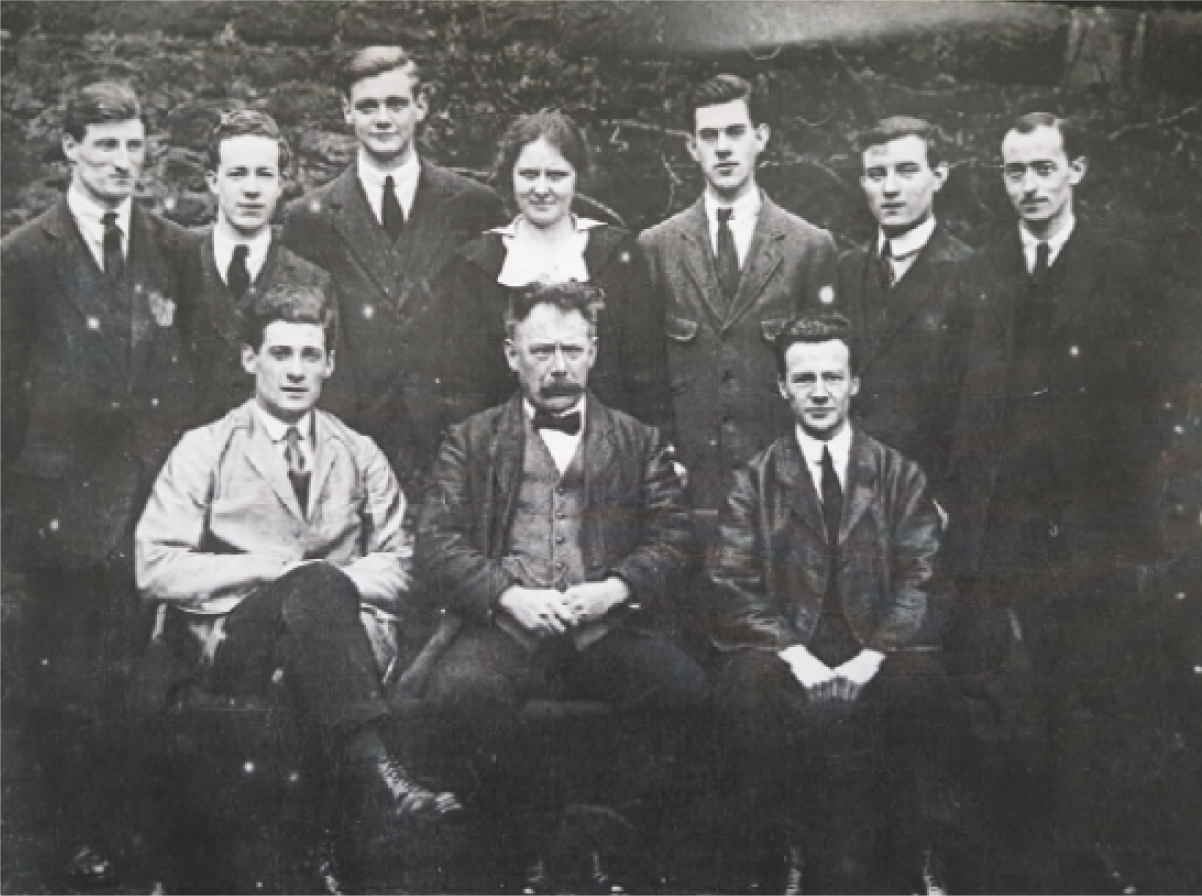

Over the coming weeks the dentists took it in turns to come to the practice to triage the patients and it was on one of those days that I decided to have a clear out of a cupboard in the corner of my office. A faded photograph of the practice staff of 1920 came to my attention, and at that moment I realised that these faces staring out at me must have been through something very similar. The years leading up to that photograph had been filled not just with the Great War but with the Spanish Flu that followed.

Robert Keith Common had been establishing himself in the practice following the death of his older partner Leon Platt in 1914. Mr Platt had been Stirling and Central Scotland’s first ‘resident dentist’ when he decided to set up his dental practice at the age of 21 in Murray Place, Stirling in 1861. As I searched the archives for this article, I realised that Mr Platt would have experienced the last great pandemic of the 19th century, the Russian Flu pandemic of 1889 – 1890, when it reached Scotland in the December of 1889. More than one million people were thought to have fallen victim to what 1950s researchers had thought had been an Influenza A virus subtype H2N2, subsequently re-categorised after sero-archeology, as Influenza A virus subtype H3N8.

As Central Scotland’s first resident dentist, Leon Platt wrote and published A Domestic Guide to a Good Set of Teeth in 1862. He became an LDS at the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh in 1879 to conform with the Dentists Act of 1878. On the 13 June 1882 he and 28 others founded the Scottish branch of the British Dental Association. After working in practice and consulting at the local infirmary, Mr Platt took on an assistant in 1892 on a salary of £3 10 shillings a week. Robert Keith Common became his co-partner in 1895 before Mr Platt’s retirement in 1902. Robert Common’s son Ralph Lawson Keith Common and grandson Robert Heron Keith Common took the practice of Platt & Common through until the 1990’s and the present-day practice still bears the names of these two pioneering dentists.

On the day this photograph was taken the Falkirk Herald reported that Charlie Chaplin’s latest film The Floorwalker was playing at the cinema, Dick Whittington and His Cat was finishing its run at the Grand Theatre, a fancy dress dance was to be held in aid of the Comrades of The Great War association at the Albert Hall in Stirling and that you could purchase a 20 horsepower Chevrolet Car for £415.

The staff of Platt & Common most certainly had no specialised personal protective equipment as their long surgery coats, stiff collared shirts and ties were the fashion of the day. During the pandemic, two years earlier they may have covered their faces with surgical gauze which was widely used at the time for surgical masks but how would they have known that the flu was coming, as all the newspapers in the latter part of 1918 were full of reports of successes at the front and the eventual end of the Great War.

Limited media coverage in 1918 (the Government of the day thought that the population had had enough bad news that year) reports the spread of flu alongside remedies for sufferers to try – including Veno’s Lightning Cough Cure as seen in the Perthshire Advertiser on 2 October. The Spanish Flu symptoms were “cough, nervousness, headache, loss of appetite and general weakness” with “pneumonia often following about 12 hours after the first symptoms appear”.

The Stirling Observer of Saturday 16 November 1918 makes mention of the closure of schools in the town and the fact that children and teachers were having a “flu holiday”. The Monday of that week had seen the end of the “Great World War”, so the paper details the celebrations that had taken place rather than dwelling on the pandemic sweeping across Europe. The Edinburgh Evening News of 4 November 1918 highlights 20 deaths in Alloa, only one being attributed to the flu. Schools were reported to be fully closed in Dundee, Kinross, and St Andrews with more than 50 deaths recorded in Dunfermline, schools having been closed there for over three weeks. As the headline states, the ‘Trail of the Flu’ was ‘still spreading in Scotland’.

On writing to the editor of the Stirling Observer on 7 November 1918, the local cinema manager says that “the hall is well ventilated and sprayed with disinfectant every day.” So perhaps Mr Common and his staff were also opening the surgery windows wide and making good use of their supplies of disinfectant. In the Glasgow Herald on 24 July 1918, the flu was reported as being “rife in the town” with “quite a number of people have come back from their holidays only to take to their bed.” It has been suggested that Port Glasgow saw the first cases of Spanish Flu in September 1918 as part of the pandemic’s second wave.

(As I write this article, in the autumn of 2020, Glasgow and the surrounding areas had been placed under special measures restricting the mixing of households and affecting 1.75 million people.)

Spanish Flu quickly spread across Scotland with mortality peaking in Glasgow in October, and Aberdeen, Dundee, and Perth in November. So, it could be surmised, that Mr Common and his staff would have been contending with asymptomatic and symptomatic patients turning up at the surgery in 74 Murray Place during the autumn of 1918 and into the following summer. The 1918-19 pandemic saw increasing mortality in young adults where previous pandemics had taken the youngest and the oldest of the population. A total of 78,372 Scottish deaths were recorded in 1918 with 17,575 attributed flu deaths (4.3 per 1000 population).

By the end of the Summer of 1919, nearly 34,000 Scots had fallen victim to the flu (the number is greater if mortality due to encephalitis lethargica which followed the pandemic is taken into account). In the early stages of the pandemic many deaths were recorded as PUO (pyrexia of unknown origin). Heliotrope cyanosis was evident on victims as extremities turned blue, bodies quickly becoming blackened as de-oxygenated blood flowed through their vessels.

UPDATE, JULY 2021: As of 19 July 2021 – so called ‘Freedom Day’ in England and the day that the Scottish mainland moved to Level Zero – 7,800 people in Scotland had lost their lives after testing positive to COVID-19, with MORE THAN 10,220 deaths having been registered where COVID-19 was mentioned on the death certificate – 33% of these deaths occurred in care homes and 61% died in hospital. When writing this article in September of 2020, no one could have predicted the devastating effect that this virus would have on a global scale. In the UK there have now been 5,473,477 reported cases of coronavirus and 128,727 deaths within 28 days of a positive test. Worldwide, these figures are in excess of 191.6 million cases and 4.1 million deaths.

At the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in the UK there were 6,818 deaths registered in a single week (7th -13th April 2020). The second wave peak saw 7,250 deaths registered in the week of the 8th -14th January 2021. With the third wave expected to peak in August 2021 there is obviously a strong case for continued vigilance and mitigation to avoid infection and transmission. 60% of people currently being admitted to hospital are unvaccinated according to the UK government’s chief scientific advisor Sir Patrick Vallance.

During this global pandemic genetic variants have emerged and circulated leading to high death rates in the US (624,861), Brazil (542,756), India (414,511) and across Europe (1.26 million). SARS-CoV-2 now has multiple ‘variants of concern’ – Alpha (UK), Beta (South Africa), Delta (India) and Gamma (Japanese/Brazil), and ‘variants of interest’ – Epsilon (California), Eta (UK/Nigeria – December 2020), Iota (New York – November 2020), Kappa (India – December 2020) and Zeta (Brazil – April 2020). The WHO has the higher category ‘variants of high consequence’(none registered at the writing of thisupdate), but it is the Delta variant that is driving the third wave in the UK.

On 2 December 2020, the Pfizer‑BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine was approved for use by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, and we were fortunate in Forth Valley to be among the first in the country to receive our first dose on 8 December. 87.9% of the UK adult population have now received a first dose of the vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech, Oxford/AstraZeneca or Moderna) and 68.5% of adults have received a second dose. Over a million daily tests are carried out daily. A fourth vaccine, Jannsen’s, will be available in the autumn.

At the time of writing this update, concerns over the lifting of all restrictions in England have been expressed by the Scottish Government but we have to return to normal life and as a profession we need to think laterally about how to eliminate the risk of aerosolised viruses now and in the future. We could avoid producing them in the first place and reduce our reliance on the air turbine, opting for electric alternatives. Many of us have started using speed increasing handpieces which negate fallow times, enhanced PPE and enhanced and extended surgery cleaning.

With the announcement of £5m of funding for improving surgery ventilation there is a suspicion that this has nothing to do with COVID and everything to do with bringing the quality of the air in our practices in line with other health care settings, something that should have been enforced 20 years ago. Is the profession being misguided by a reliance on powerful extractor fans to provide air changes when it still means minimum fallow times, FFP3 masks and enhanced cleaning. Depending on your practice location, the incoming “fresh” air may contain dangerous levels of particulate matter and nitrous oxides from road users, not to mention high levels of pollen at certain times of the year.

A version of this article was first published in Dental History Magazine, Vol 14, No 1, Winter 2020

Comments are closed here.