The effect of MS on oral health

Can the oral health of patients with multiple sclerosis be improved?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has defined multiple sclerosis (MS) as a “neurological inflammatory demyelinating condition of the central nervous system, that is considered to be autoimmune in nature”.1

In people with MS, the immune trigger is unknown; however, the target is the myelin sheath of the central nervous system tracts. The body attacks the myelin sheath and this forms scar tissue, or sclerosis, which gives the disease its name. When any part of the myelin sheath is damaged, the nerve impulses are distorted or interrupted which will produce a wide variety of symptoms, such as fatigue, tremors, numbness in face and limbs, cognitive dysfunction, and neuropathic pain that can affect a person’s everyday life2.

Multiple sclerosis can have a direct or indirect impact on oral health, be it difficulty cleaning teeth due to reduced muscular power, difficulty accessing dental care due to mobility, or the oral side effects of drugs used for the treatment of MS.

My interest in multiple sclerosis began when my mother was diagnosed with the condition in 2010. I had little knowledge of the disease, and when I began my training as a dental hygiene therapist I was curious to know the effect it has on oral health. As part of my final year of study I decided to carry out an elective project to investigate the oral problems associated with multiple sclerosis and the management of these patients within general dental practices throughout Scotland.

I found that carrying out the project gave me a clearer understanding of the disease, and by sharing my findings through this article, I hope that I can raise awareness of MS and in turn improve the care that these types of patients receive.

A study carried out by the University of Dundee estimated that there are 127,000 people with multiple sclerosis in the UK, and that each year 6,000 people are diagnosed with the condition3. They found that the highest prevalence and incidence rates of MS were observed in Scotland, with 190 cases per 100,0004. Through carrying out a literature review I could see that there is currently a clear lack of studies and research based on oral health and multiple sclerosis. Considering there is such a high population of people diagnosed with MS in the UK, there should be more research into this area.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) recently published updated guidelines for MS management in October 2014. The NICE clinical guideline 186 titled: Multiple Sclerosis: Management of Multiple Sclerosis in primary and secondary care5 has replaced NICE clinical guideline 8 published in November 2003. This updated guideline offers evidence-based advice on the care of adults with MS, and outlines how people with MS can receive better care and improve access to therapies that benefit the condition. This document outlines how the care for patients with MS requires a multidisciplinary approach which includes a variety of health care professionals, but it has not included dental care professionals within this multidisciplinary team.

A number of studies (Fischer et al.6 and Fragoso et al.7) recommend that there should be a dental professional included in the multidisciplinary care team of MS patients.

A paper titled Oral and maxillofacial manifestations of multiple sclerosis by Chemaly et al.8 discussed the three most common oro-facial symptoms presenting in multiple sclerosis: trigeminal neuralgia, trigeminal sensory neuropathy and facial palsy. They suggest that dentists should be aware of the importance of this disease in the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of oro-facial lesions, and have up-to-date knowledge of the disease.

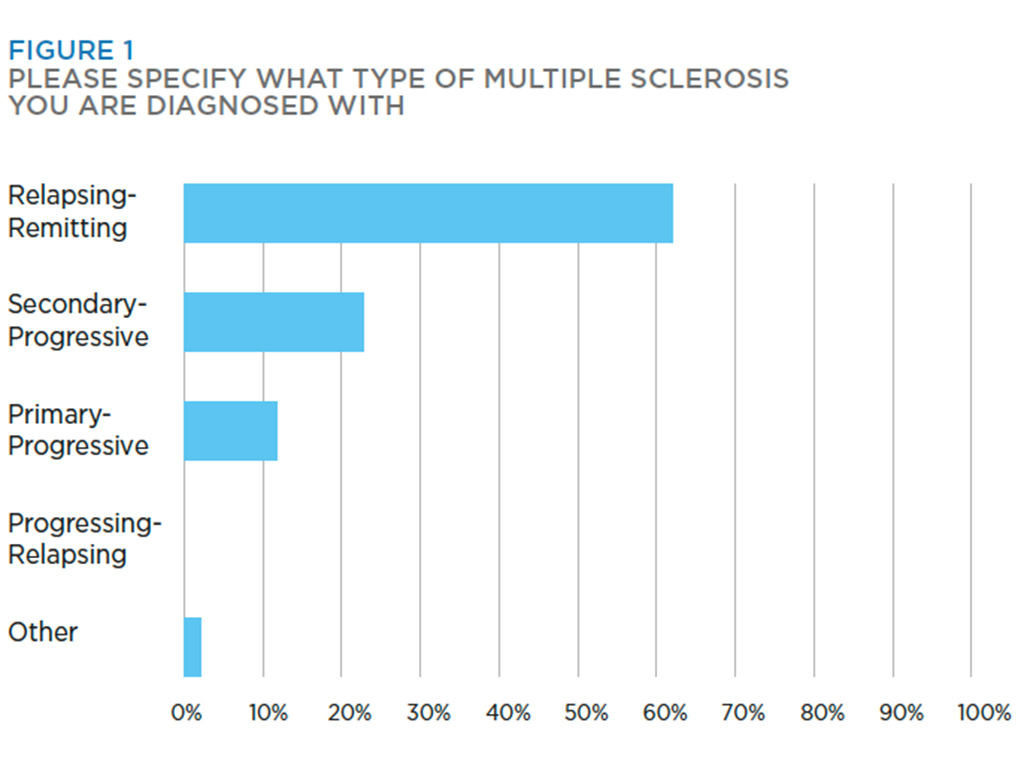

- Figure 1

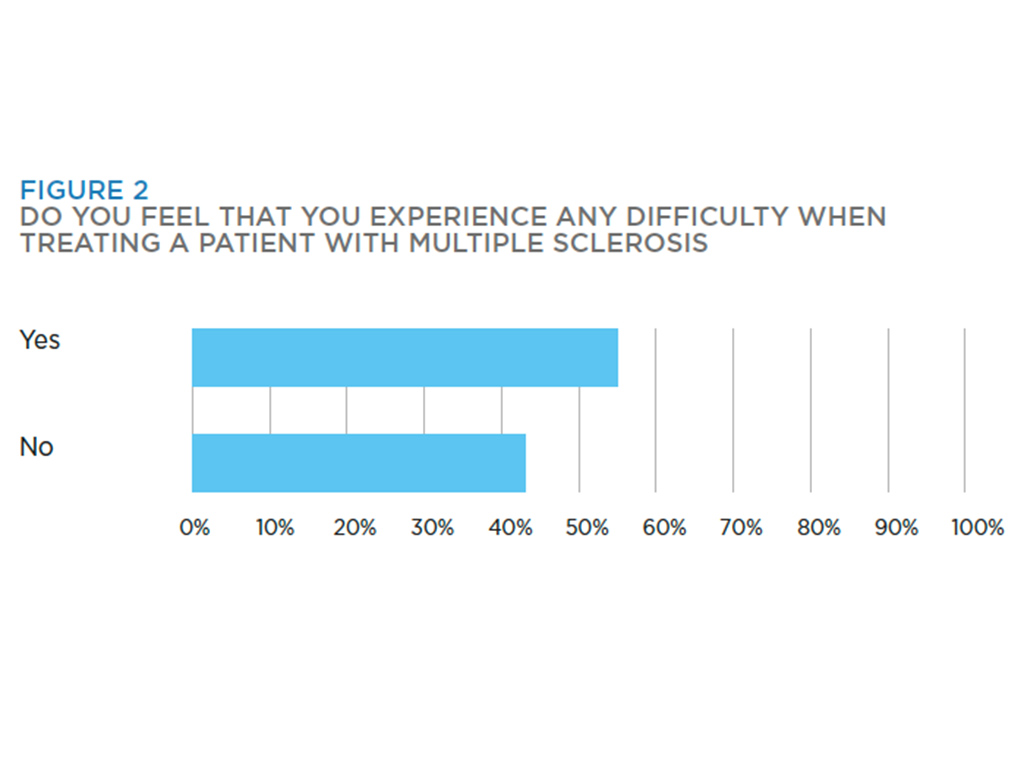

- Figure 2

The paper highlights the idea that dental professionals should be prepared to manage a clinically healthy patient that presents with the oro-facial manifestations of MS, and the possibility of referring them for further investigation. They may be involved in the diagnoses of these patients, so it is vital that they have full knowledge of the disease.

Reich and Campbell9 also looked into the various oral implications of MS and how to provide effective care to these patients. They particularly focused on trigeminal neuralgia and how it may be triggered by routine actions such as tooth brushing and mastication. They suggested that patients may be disinclined to continue oral hygiene practices if they trigger painful attacks, so it may be necessary to manage the patient’s systemic disease first, before they can achieve good oral health.

This emphasises the importance of dental professionals being included in an inter-professional care team for MS patients, as dental professionals and neurological specialists will be able to work together to successfully manage the patient’s condition and symptoms, so we can then focus on other aspects like oral health.

Elemek and Almas10 raised the topic of MS and periodontal disease in their paper Multiple sclerosis and oral health: an update. They state that “Multiple sclerosis and periodontal disease both have an inflammatory origin”, and may be linked. However, this requires further investigation. Their paper also discusses that, due to loss of muscular co-ordination and manual dexterity, there is an increased difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene, and as a result, an increased susceptibility to plaque build up which will affect the hard and soft tissues.

They recommend that patients are given specific support such as recommending to use an electric toothbrush. It is also suggested that treatment should be adapted to the individuals needs, for example, longer appointment times, with breaks for relaxation of the facial muscles and frequent urination (which is a common symptom that can occur with MS). These appointments should be carried out in a relaxed environment, and “in the morning, as these tend to be less stressful for patients with neurological problems”10.

The paper also suggests that treatment should be carried out when the patient is in remission. This is when their symptoms can partially or completely subside for a period of time, which can make treatment easier for them and the operator. The clinician should also consider the referring the patient to a hospital outpatient clinic for care. The study also states that people with MS consider their oral health to be important, as they found that a large percentage visited their dentist regularly. I believe that since these people want to have good oral health, the dental care professionals should provide tailored advice and support to these patients so they can maintain their oral health.

Baird11 designed a cross-sectional postal questionnaire- based study to determine the impact that MS has on patient attendance at dental practices, and maintenance of oral health in Leicestershire, UK. This study further supports the idea suggested in the previous paper that people with MS consider their oral health to be important. They found that compared to the general population, a higher proportion of people with MS were registered with a dentist (49 per cent compared with 88 per cent), and they also frequently attended more in the past year (71 per cent compared to 81 per cent). This shows that oral health is very important to these patients, and they may be more aware of their oral health and are conscious to take care of their teeth and mouths.

However, people with MS said that they experienced difficulties attending a dental practice and maintaining their oral health. The greatest problem that was identified which has an impact on attendance was reduced mobility. These patients may face barriers to dental care, particularly as their disability increases.

The study recommends that initiatives are required to increase awareness of the importance of oral health to the quality of life of people with MS, and to ensure that access to dental services for individuals with physical disabilities improves, so that these people receive the same access to care as the able-bodied. It also suggests that patients with a progressive disability may greatly benefit from the provision of preventative oral health care.

A study titled Oral Health Status of a population with Multiple Sclerosis by Santa Eulalia-Trosfontaines et al.12 aimed to determine the oral treatment needs of patients diagnosed with MS in a community in Madrid. They carried out a cross-sectional epidemiological study with a sample of 64 patients aged 25-77 years. They did not specify the type of MS that each individual has.

To evaluate the oral health status, they used guidelines from the WHO. They found that caries prevalence was 100 per cent in all groups, and on analysing gingival health, 65 per cent of people had calculus, 5 per cent had bleeding, and 30 per cent were healthy. The DMFT index found was very similar to that of the general population in that area. However, the gingival health status was poorer in this group of MS patients, and demonstrated that people with MS require specific assistance with their oral hygiene routine, especially in regards to gingival health.

Fischer et al.6 listed the various medications that are prescribed for the management of MS, along with the vast range of side effects that can occur, and in particular the oral side effects, such as: mucositis, ulcerative stomatisis, gingival hyperplasia, xerostomia, postural hypotension, glossitis, and immunosuppression. Drugs taken for MS can treat relapses, modify the disease course or manage the symptoms of the disease13.

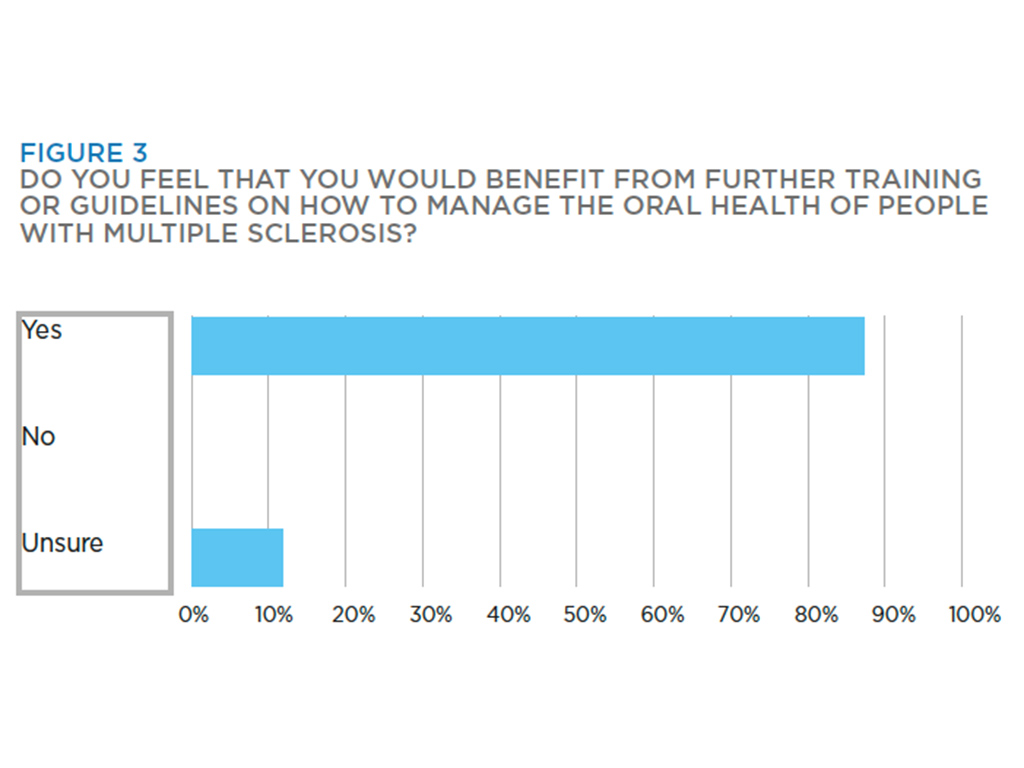

- Figure 3

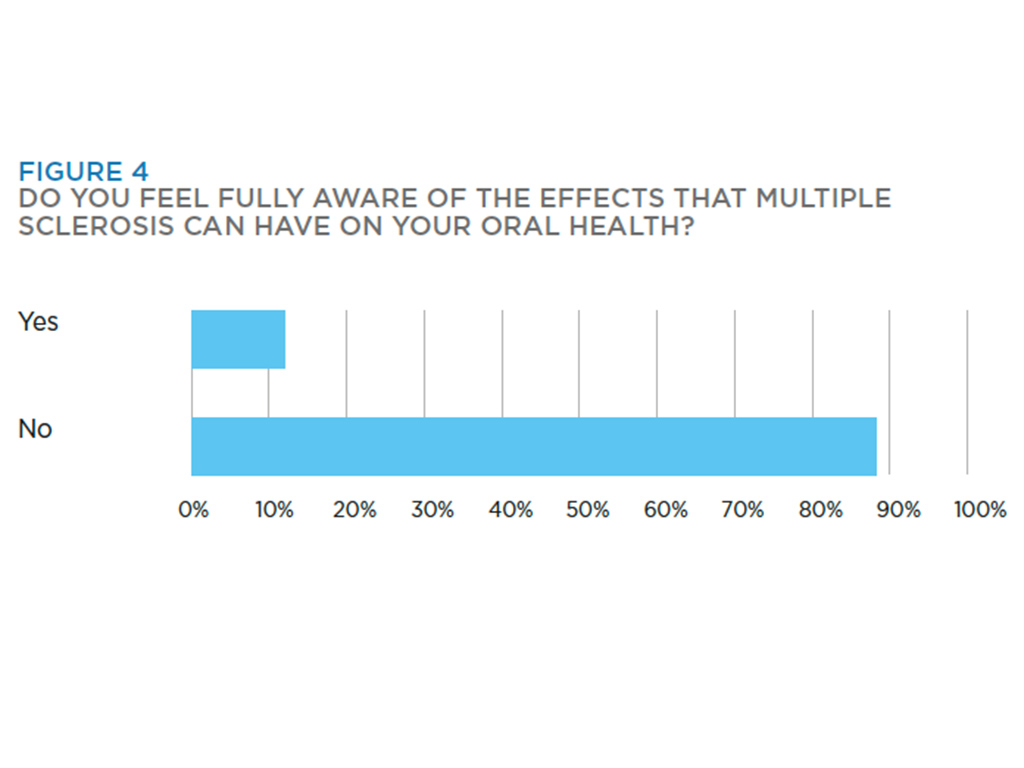

- Figure 4

Disease modifying medications (e.g Copaxone or Tysabri), and steroids for treatment of relapses are the most commonly prescribed medications. However, there are also various medications taken to manage symptoms of the disease such as Amitriptyline, Carbamazepine, and Baclofen. Alternative therapies such as aroma therapy, acupuncture, vitamins and hyperbaric oxygen therapy are popular.

In order to carry out the study for my project, a series of two questionnaires were given to patients with MS (contacted through the MS Central Online Support Group, and Revive MS Therapy Centre), and to general dental practices (to be completed by dentists, dental hygienists or dental hygiene-therapists) throughout Scotland.

I found a strong correlation between the results I had gained with the evidence I discussed in my literature review.

The majority of respondents were diagnosed with Relapsing Remitting MS (Fig 1), and the overall majority stated that they attend a general dental practice for care. The respondents with primary progressive stated that they were treated in a community dental setting, which would be expected, as these facilities offer ease of access and more appropriate specialist treatment suited to the individual patient’s needs. Baird11 supports this as he identified that MS patients face increasing barriers to dental care as their disability increases, and so we need to ensure that access to dental services for these individuals improves.

The patients felt that fatigue, weak hands and arms, poor control and co-ordination all affected their ability to clean their teeth and so can affect oral health. This supports what Reich and Campbell9 found when they looked into the various oral implications of MS and how to provide effective care to these patients. They stated how loss of muscular co-ordination and manual dexterity leads to an increased difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene.

The dental practitioners stated that they advised the use of an electric or large handle tooth brush, adapting the patient’s oral hygiene routine, use of fluoride in all forms, xerostomia advice, and diet advice. The practitioners also stated that when treating a patient they try to ensure the surgery is wheelchair and mobility-aid accessible. They also aim to have lengthy appointment times and to give them lots of breaks. One practitioner stated that they try to keep the appointments to a certain time of day.

From my questionnaires the majority of practitioners stated that they did not feel confident in treating a patient with MS, and felt that they would benefit from guidelines or training. With the clear lack of specific advice and guidelines given it may be hard for practitioners, especially with limited experience, to feel confident in carrying out treatment.

The patient respondents felt that they were not fully aware of the effects the disease can have on oral health.

Both groups of respondents suggested various things that could be done to raise awareness of the oral implications that MS can have – for example, CPD, national guidelines, posters and leaflets.

It is apparent from the results I gained from my questionnaires completed by dentists, dental hygienists and dental hygiene-therapists (Figs 2-4) that some practitioners are aware of the effects that MS has on oral health as well as the effects it may have on receiving dental care. However, with the majority of practitioners stating that they did not feel confident treating a patient with MS, it is clear that there should be more information and training available.

In regards to patients with MS, I can conclude that there should be an increased awareness of the effects that MS can have on oral health, be it the direct effects, such as trigeminal neuralgia, the effects that poor dexterity, facial pain, and fatigue can have on oral hygiene practices, or the oral side effects of medication taken for the management of the disease. Some patients are aware of the effects, but it may greatly benefit the majority patients to have an enhanced awareness.

With the increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis, especially in Scotland, I believe it is essential that dental care providers have knowledge about the disease, and the effects it has on oral health, so that they can effectively manage the patient in all aspects of dental care.

About the author

Rebecca Wilson qualified as a dental hygiene therapist in 2015, after gaining a Bachelor of Science in Oral Health Science at Glasgow Caledonian University. She currently works as a dental hygiene therapist at Spring Grove Clinic in Auchterarder and Comrie.

References

1. World Health Organization. Atlas: Multiple Sclerosis Resources in the World. 1st ed. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008.

2. NHS Choices. Symptoms of multiple sclerosis. 2014. [internet] Available at: nhs.uk/Conditions/Multiple-sclerosis/Pages/Symptoms.aspx

3. Mackenzie I.S, Morant S.V, Bloomfield G.A, MacDonald T.M, O’Riordan J. “Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the UK 1990-2010: A descriptive study in the general practice research database”, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2014. Vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 76.

4. MS Trust. Prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis. 2014. [internet] Available at: mstrust.org.uk/atoz/prevalence_incidence.jsp

5. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Multiple sclerosis: management of multiple sclerosis in primary and secondary care. 2014. (NICE CG 186), [internet]. Available at: nice.org.uk/guidance/cg186.

6. Fischer D, Epstein J, Klasser G. “Multiple sclerosis: An update for oral health care providers”, Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 2009. Vol. 108, no. 3, pp. 318-327.

7. Fragoso Y, Alves H, Alves L, Alves N, Andrade C, Finkelsztejn A. “Dental care in multiple sclerosis – an overlooked and under-assessed condition”, Multiple Sclerosis. 2009. Vol. 15, no. 9, pp. S263-S263.

8. Chemaly D, Lefrançois A, Pérusse R. “Oral and maxillofacial manifestations of multiple sclerosis”, Journal (Canadian Dental Association. 2000. Vol. 66, no. 11, pp. 600.

9. Reich M, Campbell P. “The oral implications of MS. effectively providing dental care to patients who have multiple sclerosis.” Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2010. Vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 52-55.

10. Elemek E. Almas K. “Multiple sclerosis and oral health: An update”, The New York State Dental Journal. 2013. Vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 16.

11. Baird W.O, McGrother C, Abrams K.R, Dugmore C, Jackson R.J. “Verifiable CPD paper: Factors that influence the dental attendance pattern and maintenance of oral health for people with multiple sclerosis”. British Dental Journal. 2007. Vol. 202, no. 1, pp. E4; discussion 40-E4.

12. Santa Eulalia-Troisfontaines E, Martínez-Pérez E, Miegimolle-Herrero M, Planells-Del Pozo P. “Oral health status of a population with multiple sclerosis”, Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2012. Vol. 17, no. 2, pp. e223-E227.

13. Multiple Sclerosis Trust. Drugs and treatments used in the management of MS. 2015. [internet], Available at: mstrust.org.uk/atoz/drugs.jsp.

Verifiable CPD Questions

Aims and objectives

- To investigate the oral problems associated with multiple sclerosis and the management of these patients within general dental practices throughout Scotland.

- Investigate the effects that multiple sclerosis has on oral health.

- Investigate the oral side effects of drugs taken by patients for the treatment of MS.

- Investigate the management and advice given to patients with MS within a general dental practice.

- Evaluate the possible improvements that could be done to make MS patients and dentists/dental hygienists and therapists aware of the oral implications that the disease has.

Learning Outcomes:

By the end of this article you should be able to:

- Know what type of disease multiple sclerosis is

- Know that there are different types of multiple sclerosis

- State the prevalence of MS in Scotland

- Be aware of the oral side effects of drugs taken for the treatment of multiple sclerosis

- List the symptoms of the disease that can affect the ability of a patient to maintain optimal oral hygiene

- Know the recommendations for the management of patients with multiple sclerosis.

Example Question

What kind of disease is multiple sclerosis?

A. Auto immune

B. Viral

C. Infectious

D. Blood borne

Comments are closed here.